The More Things Change

By John Mauldin

April 23, 2005

This is the text of a speech given at the Accelerating Change

2004 conference at Stanford University. The conference organizers

asked me to look out over the next 3-4 decades and offer my thoughts

as to what the future may look like. A somewhat daunting task,

and one guaranteed to failure, as the future always seems to

surprise, I nevertheless tried to peer into that dark glass.

La plus

ca change, la plus c'est la meme choses.

The more things change, the more things stay the same. What of the future? Can we

really stand here in 2004 and have some idea of what will transpire

in the next 2-3 decades? Looking at which things will not change

will give us some clues as to what will change, and some ideas

as to the future in which most of us will assuredly live.

There are three things that

over the next 40 years are not going to change.

- The innovation cycle is not

going to change - it will be with us as it is simply part of

our human progression, although it is going to increase in intensity

and frequency.

.

- The Business Cycle and its

cousins, Secular Bull and Bear markets, will not change. As long

as the business cycle remains in place, and Congress has yet

to find a way to repeal it, this tendency to go from over-valued

to under-valued markets, that started when the Medes were trading

with the Persians, will persist.

.

- Human psychology is not going

to change. Human psychology is the reason we get these cycles

and the reason we get busts and booms.

The Innovation Cycle

A Russian Economist, Nikolai Kondratieff, noticed that

we can look at cycles in the Markets, and his research led to

these long waves becoming known as the Kondratieff Wave. Many

argued that these up and down cycles lasted 56 years, 73 years

or 69.3 years. Most people, including me, look at that research

and think that it is voodoo economics. What is implied by many

of the adherents of the K-Wave theory is that the markets and

actual prices themselves are pre-determined in some fixed, almost

linear, fashion, like a predetermined destiny in a science fiction

novel. The Kondratieff Wave followers were the guys that were

telling you, if you were reading the sales letters published

in the late 80's, about the crash of 1990, the crash of 1987

or the crash of 1994.

The Kondratieff Wave disciples tried to predict the market with

a precise cycle depending upon the numbers of years, and when

they dated the beginning of the last cycle. They had figured

out that there were in fact cycles, but Joseph Schumpeter came

along and said the cycles really relate more to innovation cycles

than fixed waves in time.

What Schumpeter found was that a new innovation takes a great

deal of time to get to a 10% penetration in any given market,

but the growth from 10% to 90% is one of rapid change. The cycle

follows what we call an S-Curve and as you get to the mature

phase (or the last 10% of growth) everyone eventually gets access

to the innovation. The innovation now has complete penetration

and growth slows until it is basically in line with the economy's

growth, which is GDP (Gross Domestic Product) plus inflation.

The innovation can go into other places where it hasn't penetrated,

but once it has saturated the major world economies like the

United States or Europe, it's no longer an innovation, but a

commodity.

Harry Dent came along and said let's rework this innovation cycle

idea a little bit and try to define it better. (While his book,

The Roaring 2000s, [2] is an excellent

analysis of the innovation cycle, please pay no attention to

the ludicrous investment projections that he makes (like the

Dow going to 40,000 by 2008). What he says is that when you look

back over time, there are five phases to the innovation cycle.

First is the innovation period, second a growth boom followed

by a shakeout, then the maturity phase and then he ending or

final phase.

Let's take a look at what happens during the shakeout. What happens

during the shakeout is that a frenzy develops where too many

people are throwing money at the innovation, overbuilding and

adding way too much capacity, because that's what we as humans

do. We chase what is already hot rather than what might become

hot in the future. We throw money at stuff that's going up, create

too much of it, and then there's not enough market demand for

that capacity and you get a shakeout. It happens almost invariably

in all innovation cycles.

We are all familiar with the overdevelopment of trans-ocean fiber

optic capacity. The first few lines were projected to have (and

some actually did have) fabulous profit potential. But then everyone

jumped in and too much capacity was built, forcing a dramatic

drop in price.

This is not far different from railroads. When the first 20 mile

railroad was built in England, the investors found their profit

projections were way off. Profits were much higher than anticipated.

In fact, the early railroads were showing 100% profit in the

first year. Just like fiber optics 150 years later, too many

railroads were built and bankruptcies were soon the order of

the day.

But over time, demand caught up with supply, and more railroads

were needed and the maturity boom took over. While hard for the

investors, it was actually good for society, as all that capacity

and lower prices meant new business opportunities developed as

whole new markets opened up.

Right now for instance, in my opinion we are still in the growth

boom of the information age. We haven't seen the true shakeout

yet. No one knows how the development of broadband to the homes

of America will play out. Will it be on cable or fiber or even

on your power lines? Who will be your phone/cable/wireless/cell/internet

company in 10 years? What bundled services will we all feel we

need? The Internet was just a mini bubble compared to the potential

shakeout coming. When we see the true information age shakeout,

I think it will look like all classic growth boom shakeouts.

We will see too much capacity, prices will plummet. There will

be some major companies which will not survive and some who will

stand tall. The excess capacity will soon be swallowed up in

growing demand and then this Information Age innovation cycle

will start its mature boom phase.

Secular Bull and Secular Bear

Markets

Another cycle that will always be there is the Business Cycle

accompanied by Secular Bull and Secular Bear Investment Markets.

We use secular, not in the terms of religion, but from the Latin

word secula which means an age or period of time. What I argue

in my book, Bull's

Eye Investing, is that we shouldn't look at these cycles

in terms of price, which most people do, but rather we should

look at them in terms of valuation.

Michael Alexander wrote a great little (and far too overlooked)

book called Stock Cycles. [1] He wrote

and published it in 1999 and says, "Here's why we're going

to have this crash" completely apart from everything else.

He seems to have pegged the markets with the way he views cycles.

Alexander finds that these valuation cycles in secular bear/bull

markets run anywhere from 8-17 years and he forecasts that we're

currently in the middle innings of a secular bear cycle. In the

past a secular bear never stops in the middle of going down,

it always goes to the full extent of the pendulum. There will

be bull market rallies during a secular bear market, but the

next secular bull market will begin after we go through what

I call "The Puke Factor," when very few want to talk

about or own equities anymore.

The race is not always to the swift or the battle to the strong,

but that is the way to bet. You don't want to make a long shot

bet on the slowest horse winning when you are going to a horse

race. You want to look for the horse that is likely to win that

day. History shows us that Bear Markets always start with high

price to earnings (P/E) ratios and Bull Markets always start

with low price to earnings ratios. The lower the price to earnings

ratio at the beginning of the period, the higher your returns

are going to be when the price to earnings ratio tops out.

Where (in terms of P/E) you start investing makes a huge difference

as to what your results are going to be over time. In fact, there

have been periods of 20 years or more that a market index has

made zero returns. That's not what the guys tell you down at

the office when they are trying to get your money into their

mutual fund. There's never a money manager that will tell that

today is not a good day to invest in their fund. Me included.

It's always a good day to invest, although history shows us that

some days are better than others.

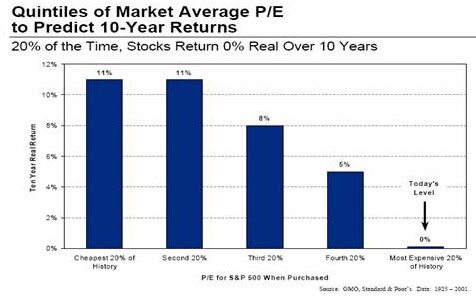

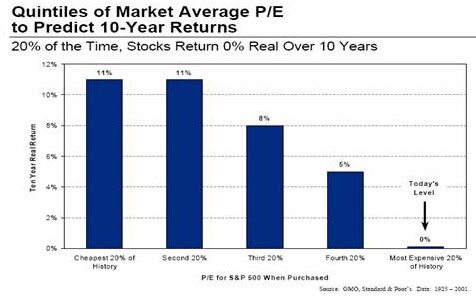

Here's a study done by Jeremy Grantham, where he breaks up the

years from 1925-2001 by looking at the average price to earnings

level for the year. He then groups the years based on this valuation

into 5 different buckets. The highest price to earnings years

was labeled the "most expensive 20% of history"; the

lowest price to earnings years was labeled the "cheapest

20% of history." What he found is that over the next 10

years the cheapest or second cheapest quintiles had an average

compound return of 11%. That's when your financial planner tells

you to write a 10%-12% return expectation into your retirement

planning model, because, "Look, see what the market has

done for the past 10-15 years?"

However, if you invested in

the most expensive quintile in history, the average compound

return over the next 10 years was zero. That's not a good deal,

except for the managers charging a fee to manage your money.

So, getting into the market during times of low valuations has

been the best choice in the past.

Markets are volatile. What you find is that over the last 103

years the Dow Jones Industrial Average's annual return was between

+/- 10% over 30% of the time. Over 70% of the time, the annual

return was either above 10% or below 10%. [3]

A company called Dalbar has done some studies that show the average

investor does not do nearly as well as the average mutual fund

does because they chase returns.[4] They switch

into a fund that is "hot." Chasing returns is momentum

investing - if something goes up, let's invest in it. What happens

is, people typically get into something at the top, then it turns

down and they get out. This strategy is essentially a formula

for buy high, sell low and is a poor way to invest.

Let's talk about the real effect of compounding. Take the last

103 years from 1900-2002, the markets simple annual arithmetic

average return is 7.2%. That's what the brokers and other salespeople

are trotting out when they try and raise money. The problem is

over the same period of time if the returns are compounded annually,

the average is only 4.8%. Keep in mind that this is the compound

average over long periods of time (in this case 103 years). This

negative compounding effect, if you will, stems from the fact

that if you are down 33% early on, you are going to have to make

50% to bring you back.

In my book or at www.crestmontresearch.com, there is a chart

for Taxpayer Nominal Returns over the last 103 years. You can

see in this chart what your returns would have been for any given

period of time starting with any year you choose. The chart is

color coded; the reds are below zero returns; pink is between

zero and 3%; blue is between 3% and 7% and light and dark green

cover the periods with annual compounded returns over 7%. The

annually compounded numbers are in white or black and indicate

whether the price to earnings ratios were falling or rising during

that period.

Surprise, Surprise...you find out that almost all the light and

dark green squares are periods of rising price to earnings ratios,

or black numbers. However the red and pink squares are predominately

periods of contracting price to earnings ratios, or white numbers.

This graph also helps visualize the long term historical returns

patterns in the market. You can easily find periods of 10 or

15 years where you're making 0-3% net. This tells me when I see

a period of high price to earnings valuations, better returns

might be found elsewhere.

There is always a Bull Market somewhere in something. When you're

in Secular Bear cycles, become more concerned about protecting

against a loss and try for absolute returns; when you're in Secular

Bull cycles, buying an index for relative returns has historically

done well in the past. What I mean by that is, if price to earnings

are at low valuations, and you put money in index funds historically

you will do well even if there are events like October 1987 because

as the price to earnings rises it will hopefully be due to the

price going up rather than earnings coming down. All you need

to do is follow the market because the market's going up and

if you actually beat the market by active management, you did

a good job.

Now, if we are in a Secular Bear cycle, you want to do just the

opposite. In Secular Bear's, market valuations are going down

over time. Now you want to focus on absolute returns and the

need to protect against negative returns. Your measure, in a

Secular Bear cycle, is a money market fund. In a Secular Bear

cycle, the person who loses the least is the winner. That's just

the way things are. Typically, you could have beaten stock market

index returns dramatically in this period simply by being in

bonds.

Human Psychology

Let's talk now about Human Psychology, which will always be with

us. Last year's winners of the Nobel Prize for Economics were

two psychologists, who came up with the sometimes obvious thought

that investors are irrational. Their contribution, however, was

that humans are not just irrational, but predictably irrational.

We keep on making the same mistakes time and again. I am reminded

of one of my wife's favorite quotes, "Insanity is doing

the same thing over and over and expecting different results."

One example of behavior patterns which drive the markets is the

"home field advantage." We bet on our home teams. I

live in Dallas. It would be reasonable to expect, and bookies

make lots of money on the fact, that people in Dallas will bet

on the Dallas Cowboys more than on the Saint Louis Rams. Those

of us in Dallas read the local papers and thus know more about

the Cowboys than any other team. Because we know more about them,

we think they are a better team than they in reality are.

Researchers have done studies where they ask people to play the

following game. A deck of 52 cards is held up and the participants

are told, "I will show you a card and put it back into the

deck. If your card is picked from the deck at random, you get

$100. To play the game will cost you $1." What will you

sell that card for? The researchers find that a person will sell

that card and their chance at the $100 prize on average for $1.86.

This is actually a reasonable price but a little low. The probability

of a payout is 1/52 which comes out to $1.92.

Next, the researchers shuffle the deck again and let the participant

pick a card from the deck. What will people sell their card for

now? Closer to $6.00. Because they touched the card, they feel

they are intimately aware of and have a connection to the card.

"I've touched this card. I've studied this card and I know

its value." An interesting side note is the researchers

found that MBA students felt their chance was worth closer to

$9.00.

Researchers have also found the same phenomena with institutional

investors. When asked, "Which market do you think is going

to go up more in the next 5 years?" they tend pick their

home countries. Why? Because they know that country. They are

familiar with it. In the 90's, investors knew their stock, "I've

examined it and know it history, I've talked to the CEO, I've

looked at all of the data, and I know it."

And then they ride it right on down because they think that because

we know something and we've studied something that it has more

value. Wrong. Maybe it does and maybe it doesn't. But knowledge

of a situation does not in and of itself create value. That's

not to say we shouldn't be studying and reading about all our

investments, but we have to recognize that we have a bias about

what we know.

We also have what's called a "Confirmation Bias." We

like to read people that think like us. We tend to run around

with people that think like us because they help reconfirm that

we are right. My "Thoughts from the Frontline" newsletter

is a very self-selecting thing as most of the people who read

me do so because they like what I'm saying. It reinforces their

beliefs. If they don't like my ideas and views on global economic

issues, they unsubscribe. It's merely a confirmation bias. Very

few people read me to get another side of the story. That's just

the way human nature is.

One of the things I try to do in my letter and my "Outside

the Box" is present people with the other side of the story.

I find the best way to internally establish my ideas is to be

challenged by others ideas. Working through well-thought essays

which disagree with me forces me to constantly re-evaluate my

positions.

Another concept is "hindsight bias." How many of us

know that the dotcom era was a bubble? How many of us knew in

1999 that the dotcom era was a bubble? Everybody was telling

us that this time its different and using some quite creative

arguments to prove why, but one of the things that you need to

run away from is when anyone tells you that this time it's different.

Another thing we do is "extrapolate." We take a piece

of data and we extrapolate it into the future. I'm going to give

you a little business model here, something that should be successful.

Take the average Wall Street analyst' earnings projections [5], cut them in half, and hire three MBAs to justify

why you are cutting those prices in half.

That's one day of work. Then, for the next 29 days, you go work

on your golf handicap. At the end of the year, you should be

the most accurate analyst in the country. People will pay you

tons of money, and your golf handicap will be in single digits.

That's not a bad business model.

Why is this? Professional analysts take recent trends and they

project them into the future. By the way, if the trends are down,

then you want to add some to it because the professionals will

project the lower trend for too long as well. Even professionals

take the current trend and the current data and push it into

the future. That's one way we get extrapolation. The better plan

is to take the data, read tons of it, and then bring inferences

out of it to try to see the patterns.

What Will Change?

Let's talk about what will change. The pace of innovation is

going to change. The pace of globalization is going to change.

The shift from a US-Centric world to a more balanced world is

going to change.

First, let's look at the pace of innovation. There have been

many major innovation cycles - think Agricultural, Commerce,

Cotton, Textile, Railroads, Industrial, Mass Production and Information.

Each of these has 5 periods, the innovation, a growth boom, a

shakeout, a maturity boom cycle and the final phase. Just to

give you an idea of what we mean by the industrial economy -

that included coal, education, iron, railroad, steel and the

telegraph.

The Mass-Market economy was also composed of "smaller"

innovations in the 1900's. The airline, broadcasting, education

(secondary), electric power and appliances, motor vehicles, petroleum,

synthetic fiber and telephone were all part of the mass-market

economy. We still have a mass-market economy, but now it's in

more of a mature phase. We see much of what was novel only a

few decades ago as simple commodities today. In the 80's, the

information age started and again there's lots of components

to the information age, but historians will look back and see

it as one big movement. We are well into the growth cycle, as

I noted above, and waiting for the shakeout phase to rear its

head.

We will look more at the innovation cycles in a moment, but first

let's shift gears and look at a few other important areas.

Demography

Another thing that is cooked into the books is demography. We

can make a fairly realistic projection of how many people will

be over 60 in 20 years by looking at how many people are over

40 today. By projecting birth and death rates, which change slowly

over time, we can get a fairly realistic handle on world population

trends. And what we see is an aging Europe, Japan and America

and an explosion of population in Asia.

This will have a major effect on the pace and shift of globalization.

The developed countries have gone from about 33% of world population

in 1950 to the 18% range right now. The current developed countries

will be 12% of the population in 45 years. The underdeveloped

countries are going to grow to roughly 87%. That's a huge demographic

shift.

Another important shift will be in the 10 major Islamic countries.

By 2050 their population will be about the same as the developed

countries. Today, Russian has 145 million people and at its current

rate it will be 100 million it 2050. Iran and Iraq currently

have 87 million people combined. Today they are roughly 60% of

the population of Russia, and in 2025 those two countries will

have 10 million more people than Russia. Iran alone will have

a greater population than Russia in 45 years. How do you think

a nuclear power and militaristic power like Russia is going to

be able to deal with that change? It makes me wonder if the reason

Iran wants nuclear power is simply the US?

Yemen will be bigger than Germany in 45 years. Yemen is a small

country, where will they go?[6] We have already

witnessed the largest migration of human population in human

history. Over 200 million Chinese have moved from the interior

and the west to within 90 miles of the coast in the last 20 years.

That is almost too large to grasp. It is as if half the population

of the middle part of United States decided to move to the coast

in the next 20 years.

What implications does demography have on the aging population

of the world? The population over 60 years old will grow dramatically

in the developed world from 2005 to 2040. The US will go from

16% today to 26%; Japan grows from 23% to 44%; Italy from 24%

to 46%. Those are major problems which will affect worker productivity,

health care and strain the economy. The percentage of GDP that

countries will have to tax if they keep the promises they made

to the retirees will be a problem, as there will be less workers

to pay into the pay as you go retirement systems. France will

be at 64% and Germany will be at 60% of GDP just for social services,

without adding other government costs such as education, military,

roads, etc.

Do you think young people are going to stay in France or Germany

and see tax rates of 75% or more? The strain on the systems clearly

can't work.[7] Europe and Japan are destined

to go through enormous social and economic strains. Farm subsidies,

a deeply ingrained part of Europe and Japan, will be cut

or done away with. How can I say this? There will be more elderly

voters who want their health care and pensions than there are

farmers. Just the threat of a drop of a small part of farm subsidies

in France brings out farmers who riot, block roads and create

mass protests. Think about what will happen as they lose those

subsidies over the next 15-20 years.

While not as bad as Europe and Japan, the US has its own problems

coming down the demographic highway. The US will be forced to

change its social security system. If we don't change it by the

end of 2005, my prediction is that it will not change until 2013.Whoever

is elected president by either party in 2008 will not touch the

"third rail" of politics (social security) until a

second term. By then, the problems will be much bigger.

Social Security in the US can be fixed. The real problem is Medicare

and health care. Health care costs will rise from 14% of GDP

in 2003 to 17% in 2010 and keep on rising as Baby Boomers need

more care and as better and ever more expensive solutions are

found to keep us healthy. A reported $40 trillion dollar deficit

looms in front of US tax-payers. The options are not pretty.

We can raise taxes significantly over time, cut back on other

spending like our military, farm subsidies, education and welfare,

or cut back on health care. What politician will want to run

on that platform?

This will all produce a shift of economic power to the East.

China, India and the rest of Asia will come to the fore by the

middle of this century. This shift will be forced because of

the Economic, Political and Demographic changes which will happen

in the West. The United States and Europe have guaranteed our

baby boomers and our elders "X" amount of our GDP.

We have bet the farm on our future, we haven't saved enough money

for it and we're expecting our kids to pay it. That's going to

force fundamental restructuring. China, India and other parts

of Asia don't have those obligations because the elderly population

is a much smaller percentage, so they will be able to devote

more of their dollars to research and to economic development.

The sheer shift of assets into research and development will

give the Asians an advantage. They have an advantage in terms

of demographics, but not too much over the US. China, by the

way, is going to have demographic problems within 20-30 years.

Governments are the problem, they are not the solution. Less

government, from a business standpoint, generally means less

cost and that is a better thing. The less money that you are

paying in taxes, the less money your corporations and your investors

pay in taxes, the more the customers are going to be able to

pay to put your products on the table and in their homes. Not

to mention the more money to return to investors.

The change that I think is really coming over the next four decades

is the demise of centralized governments because they are not

"profitable." They don't work in a globalized and industrialized

world society with mobile capital and mobile people. What we

will see is the rise of the sovereign individual, which is a

very uncomfortable change; governments won't willingly give up

that power. The "spread" between the rich and poor

will increase as well, making the politics of envy all the more

susceptible to politicians who love to demagogue.

Now, let's look at what I think will be a positive force, and

one that will help us get through these problems. As I noted

above, I think in another few years that we will see a shakeout

of the Information Age and then a follow-on maturity boom which

will last another 20 years. Looking at past such cycles, the

boom should be every big as big as the innovation boom was in

1980-2000. That in itself will create a world-wide technology

and productivity boom, creating jobs and wealth.

Such a boom is not all that hard to forecast, and it will be

welcome. But I think there is a surprise coming, something that

we have not seen in human history. I believe we will get multiple

innovation booms overlaid on top of the maturity boom of the

Information Age.

Currently, the Biotech Revolution is still in its initial innovation

phase. It has barely made an impact in comparison to what most

experts think it will in the next 15-20 years. In another few

years, we will start to see the growth boom from the Biotech

Revolution kick in. Amazing new drugs and processes will change

the way we live. We will live longer and healthier lives, eat

better and less expensive foods, clean up our waste (and our

waists) and even develop new energy sources.

Coming

right on the heels of the Biotech Revolution will be the Nanotech

Generation - a world of unbelievably small machines and processes.

What sounds like science fiction today will be reality in 20-30

years.

$100 oil is not the problem, it's the solution, as converting

to new energy sources is a huge growth dynamic. The need for

new and cheaper sources of energy will compel all sorts of innovation

and new invention. The steam engine was basically developed to

pump water out of coal mines, as England needed new forms of

energy to substitute for dwindling forests. Yet the collateral

uses propelled the British Empire to its peak of economic power.

Think of the resources and the money and the innovations that

will come to play with the development of a new energy paradigm

for the world.

For the first time in history, we could get multiple major Innovation

Booms all creating change and economic progress at the same time.

It would be like Watts and Edison and Ford and Bell and Whitney

and Crick all doing there thing at the same time. How different

might our world have been? How would things have progressed?

Just imagining the possibilities will give you some idea of what

may lie in our future.

Yes, I did outline a number of problems in our future in this

speech. But there have always been problems of one form or another.

The key to understanding the changes that are in our future,

to finding profitable investments, is not to ignore the problems,

but to figure out how they will be solved and then to invest

in the solution.

La Jolla, Houston

and Home(!)

I am in La Jolla for my annual Accredited Investor Strategic

Investment Conference that I run in conjunction with Altegris

Investments. Quite the line-up of speakers: Richard Russell,

Rob Arnott, Paul McCulley, Andy Kessler, Mark Finn and your humble

analyst, plus a number of funds and managers. We are recording

the main sessions and I will let you know how to get a copy of

those sessions in a future letter.

For those interested (and who qualify), I write a free letter

on various topics concerning hedge funds. A new one will go out

next week on the topic "Are There Too Many Hedge Funds?

I take a somewhat controversial position, which will not surprise

long time readers. If you are an Accredited Investor (basically

net worth of more than $1,000,000) you can go to www.accreditedinvestor.ws and sign up. In conjunction

with Altegris Investments (and Absolute Return Partners in Europe)

we offer information about and access to hedge funds and other

alternative investment products. You can read on the web site

more details about how the process works. (In this regard, I

am president of and a registered representative of Millennium

Wave Securities, member NASD. See specifics disclosures and risks

below.)

As always, I hate to limit access, but we must work within the

rules, which limit access and information on hedge funds to those

with specific net worth. Next time you see your congressman,

tell him how stupid it is to have rules written 60 and 70 years

ago dictate what you can and cannot invest in. There would be

riots if we limited investments to just white males over 50,

yet we think nothing about drawing a sharp line between those

who are "rich" and those who are not. Archaic.

After speaking in Houston Tuesday and Wednesday, I will be home

for most of the next month, and I am ready to be home. My travel

in April has been brutal, and I look forward to being able to

get some major writing and research projects done. Plus, the

Dallas Mavericks are in the play-offs and this year it looks

like they might get past the first round. We'll see if Dirk Nowitzski

and team can get us past the first two rounds.

Footnotes:

1.

Michael A. Alexander, Stock

Cycles: Why Stocks Won't Beat Money Markets Over the Next

Twenty Years (Lincoln, NE: iUniverse.com, 2000).

2. Dent,

Harry S., Jr. The

Roaring 2000s: Building the Wealth and Lifestyle You Desire

in the Greatest Boom in History. New York: Simon & Schuster,

1998.

3. Study

done by Crestmont Research, www.crestmontresearch.com.

4. Dalbar

Inc., www.dalbar.com.

5. David

Dreman, "What Earnings Recovery?" Forbes (July

8, 2002).

6. Martin

Barnes, The Bank Credit Analyst (March 2003), www.bcaresearch.com.

7. Richard

Jackson and Neil Howe, "The 2003 Aging Vulnerability

index: An Assessment of the Capacity of Twelve Developed Countries

to Meet the Aging Challenge," Center for Strategic and

international Studies (CSIS) (March 2003).

Your 'still working on his speech for tomorrow night' analyst,

April 22, 2005

John Mauldin

email: John@frontlinethoughts.com

Mauldin Archives

Copyright ©2005

John Mauldin. All Rights Reserved.

Note: John Mauldin is president

of Millennium Wave Advisors, LLC, a registered investment advisor.

All material presented herein is believed to be reliable but we

cannot attest to its accuracy. Investment recommendations may

change and readers are urged to check with their investment counselors

before making any investment decisions. Opinions expressed in

these reports may change without prior notice. John Mauldin and/or

the staff at Thoughts from the Frontline may or may not have investments

in any funds cited above. Mauldin can be reached at 800-829-7273.

MWA is also a Commodity Pool Operator (CPO) and a Commodity Trading

Advisor (CTA) registered with the CFTC, as well as an Introducing

Broker (IB). John Mauldin is a registered representative of Millennium

Wave Securities, LLC, (MWS) an NASD registered broker-dealer.

Millennium Wave Investments is a dba of MWA LLC and MWS LLC. Funds

recommended by Mauldin may pay a portion of their fees to Altegris

Investments who will share 1/3 of those fees with MWS and thus

to Mauldin. For more information please see "How does it

work" at www.accreditedinvestor.ws. This website and any

views expressed herein are provided for information purposes only

and should not be construed in any way as an offer, an endorsement

or inducement to invest with any CTA, fund or program mentioned.

Before seeking any advisor's services or making an investment

in a fund, investors must read and examine thoroughly the respective

disclosure document or offering memorandum. Please read the information

under the tab "Hedge Funds:

Risks"

for further risks associated with hedge funds.

Recent Gold/Silver/$$$ essays at 321gold:

Apr 26 Why Gold Is the Smartest Move You Haven't Made Yet (But Still Can) Brother Carlton 321gold

Apr 25 Hi Ho Silver Morris Hubbartt 321gold

Apr 25 Crazy-Overbought Gold! Adam Hamilton 321gold

Apr 22 Antimony is Critical for Military Metals Corp, too Bob Moriarty 321gold

Apr 22 Sell America & Buy Gold Stewart Thomson 321gold

Apr 18 Gold Stocks: When Does The Rally End? Morris Hubbartt 321gold

|

321gold

Inc

|